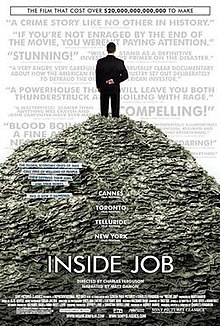

My interest in the crisis probably began with a series of shows from the always excellent This American Life. The first aired in May of 2008; it was called “The Giant Pool of Money” and its focus was on the housing crisis. The episode explained in as simple terms as possible how the housing bubble burst. Later in October, This American Life aired a show plainly titled, “Another Frightening Show about the Economy.” Even though I had heard the terms collateralized debt obligation, derivatives, and credit default swaps before listening, I didn’t really know anything about what those terms meant until I heard these shows. (Confesion: I still couldn’t really explain what most of those terms mean in much detail.) Then I read William Cohan’s House of Cards: A Tale of Hubris and Wretched Excess on Wall Street. Cohan’s book was an in-depth analysis and story of the fall of the colossal Bear Sterns. I finished it but was sort of bored by it: too much uninteresting detail. It easily could have been half as long. While I’ve enjoyed most of the films and books, one I hated was Guaranteed to Fail, a detailed account about the housing crisis and the failures of Fannie Mae and Freddy Mac—both initially created by and ultimately backed by the federal government so that they were quite literally “guaranteed to fail.” Written by economic professors from NYU, the book, which I heard about on The Daily Show, was far too jargony and mired in professor-speak. It was certainly not written for a general audience. Aside from Confidence Men and Boomerang (also Lewis’s The Big Short), one of my favorites was the documentary Inside Job, which I wrote about elsewhere on this blog. It was the most engaging and, frankly, entertaining of them all.

Here’s a brief overview of what I have learned about why things went the way they did:

- President Reagan instituted a series of deregulations in the 1980s that weakened the government’s ability to oversee Wall Street. These deregulations continued under both Bushes and the Clinton administration.

- Inside Job explains that academic economists advocated deregulation for decades and most opposed new regulations even after the crisis.

- Also in the 1980s, the Federal Reserve created historically low-interest rates in order to enable people to spend more and improve production and the economy; ultimately the low-interest rates had the impact of accruing unprecedented debt for millions and millions of people because it was easier than ever in the 1990s and 2000s to buy more than people could afford.

- Because the stock market and housing were performing so well in the 1990s and early 2000s, most Wall Street firms began leveraging, which means that they didn’t use their own money to make investments—they borrowed it. When the market performs well, leveraging is highly profitable. Of course, the market does not always perform well and lots of companies could not repay debts they owed.

- The rating agencies (Moody’s and Standard & Poors) clearly inflated the ratings for many if not most of the Wall Street firms. They gave the highest AAA ratings to companies that were over leveraged and taking on more and more very risky debt. Lewis makes the convincing (and seemingly obvious) argument that one of the main reasons the rating agencies failed to rate the firms properly was that since the rating agencies pay substantially less that Wall Street firms, all of the smartest people went to work for Wall Street.

- The creation in the late 1980s of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), which are basically bets on how well loans and bonds will perform. CDOs are broken into “tranches” or levels based on how risky the loans or bonds are. One of the reasons these lead to the housing crisis was that Wall Street firms poured billions into what they believed were safe CDOs, the highest level—that there was a safe tranch was a myth.

- It was quite clear after reading Michael Lewis’s book The Big Short that ignorance was one of the main reasons the crisis occurred. Many investors and Wall Street firms had little or no knowledge of the complicated investments they were making.

- Another way to interpret the firms’ inability to see how risky their loans and bets were becoming is to argue that it was pure hubris. They thought they were invincible, and their seeming invincibility led them to foolish acts.

- Fannie Mae was originally created during the Great Depression to provide local banks with federal money and encourage home buying, but in the late ‘60s it was turned into a private corporation that was backed by the federal government. The government would hold the companies up no matter how disastrously they performed.

- The Clinton administration passed legislation that encouraged Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and others to loan money to people who couldn’t afford them by lowering interest rates and introducing adjustable rate mortgages, where monthly payments were initially low.

- Lots of investment firms and mortgage lenders pushed subprime loans onto people who clearly couldn’t afford them. Lewis tells of a migrant worker in California making about $20,000 a year who was able to buy a $700,000 home with no money down.

- While their CEOs continue to deny culpability, it’s clear that, at least on some level, fraud was involved. Some people clearly knew that they were selling crappy loans, CDOs, and derivatives to clueless investors. Very few people, and none of the big firms’ CEOs at least to my knowledge, have been prosecuted.

- Inside Job also makes it clear that many if not most of the academics who were parts of the Reagan, Clinton, Bush, and Obama Whitehouse’s had conflicts of interest in that they were advising their presidents on economic policies while also being paid to write reports or paid consulting fees from various Wall Street firms whose interest would be better served with less regulation and policies that bailed them out.

- President Obama’s administration has done little to nothing about remedying the problems that underlie the crisis. The Dodd-Frank bill was finally passed this last summer but it so full of loopholes that most people say it will have very little or even no effect.

No comments:

Post a Comment